So much has been said about the plastic crisis that it seems there’s nothing left to add. But a group of enthusiastic engineers is collecting used bottles, grinding them into something resembling coloured shavings, and then printing new items from the result. Not in a factory – but on campus. The website liverpoolname.com discovered this and felt compelled to tell you about it.

Frankly, Liverpool looks somewhat untypical as a laboratory for the future of plastic recycling. University researchers and large corporations work here, and now an innovative packaging centre has also opened. Yet, despite all this enthusiasm, not everything is rosy: some technologies remain prototypes, and some plastic types are resistant to recycling even by the boldest extruder setup. Nevertheless, the story is interesting – because it hints at a way to make something useful out of Liverpool’s waste.

Campus Recycling: When Students Become the Engineers of Tomorrow

Engineering romance as it is: a mechanical engineering student stands next to a homemade shredder, feeds a plastic bottle into it, presses a button, and watches as the waste turns into raw material. All this is not a metaphor, but a project by a group of students from the University of Liverpool who decided: enough talking about ecology, it’s time to take action with our own hands.

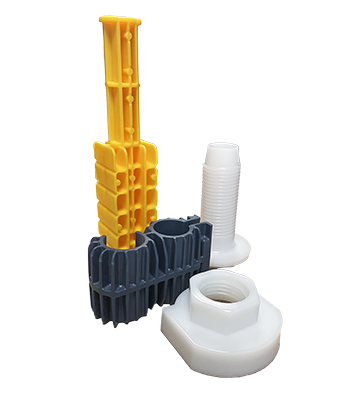

In the campus basement, they assembled a system capable of shredding plastic waste and converting it into material for 3D printing. The output is a coloured filament that can be used to print a new component, a souvenir, or, say, a charging cable holder. It sounds modest, but the essence here is not in the scale, but in the principle: waste is not taken away to nowhere, but completes a full cycle on site.

One of the project participants, Jack Nesbitt, explains:

“The goal is to turn collected plastic into raw material for new products through the design of a shredder and extruder.”

It’s not quite what we imagine when we hear the word “university,” but it aligns perfectly with the spirit of the time – when engineers must work in the proving ground of the real world.

From Waste to 3D: How the Closed-Loop Technology Works

Liverpool-style recycling is when a plastic lid can be turned into a new bench, a tile, or even an architectural element. And these are not futuristic fantasies, but real technologies already being tested in the TRANSFORM-CE project. It is managed, in part, by researchers from the University of Liverpool, and it operates across several countries.

The core lies in two approaches. The first is familiar from the previous section: shredded plastic is fed into a 3D printer to make small items or components. The second is compression moulding, or roughly speaking, forcing mixed, often lower-grade plastic into large moulds. This is how, for instance, garden furniture or street furnishings are created.

But a question immediately arises: what about household plastic – the kind left over from washing capsules or yogurts? Most of this packaging is still reluctantly accepted for recycling. At the municipal level, this depends on how sorting is organised and what raw material is deemed suitable. Liverpool is doing better than the national average in this regard, but it is unlikely that all types of plastic are recycled here.

However, the idea of the “closed loop” is gradually moving from laboratories into the streets – with all the difficulties that come with it.

Business and the City: Innovation Hubs and New Packaging

While students are assembling extruders, a serious facility is opening in Liverpool’s business centre – the Sustainable Packaging Centre. It was launched in Liverpool Science Park, and the project is run by the CPI organisation – something like a technology broker between science, manufacturing, and retail.

Why all this? To help companies switch from traditional packaging to recyclable or biodegradable alternatives. And most importantly – not just to replace one film with another, but to understand how that plastic behaves when attempts are made to reuse it.

“Currently, only 5% of plastic packaging in the UK is actually recycled,”

says Darren Regeb from CPI. You have to admit, for a country with “green economy” ambitions, this seems somewhat inadequate. That is why Liverpool, with its scientific background and industrial sites, was chosen as the base for new experiments.

Major brands have also joined the initiative. For example, Unilever is testing packaging made from recycled HDPE – the same rigid plastic used for jerrycans, shampoo bottles, and cleaning agents. The goal is to learn how to incorporate secondary raw materials without compromising product quality.

The city also has a clear goal: to increase the recycling rate for municipal waste to 65% by 2035. It sounds great, but as for the implementation – time will tell.

What Hinders and What Helps Scale Ideas

In every story of ecological breakthroughs, there comes a moment when one must honestly discuss the brakes. In this case – the things that prevent initiatives from moving beyond campuses and tech parks.

First: the quality of recycled plastic. If you think that a new bottle can be made from an old bottle – no, not always. The material loses some of its properties after the first cycle. And even if it is perfectly suitable for a bench, it may not always be suitable for food packaging. That is why large companies like Unilever are testing recipes and ratios to find the golden mean between eco-friendliness and functionality.

Second – the economics of the process. Collecting, sorting, washing, grinding, converting into something new – all this requires resources, people, and time. If you add to this the cost of equipment, it becomes clear why not every community is ready to launch a full cycle in its own district.

And third – habit. The good old laziness to sort, ignorance of disposal rules, and sometimes the lack of infrastructure make even the best initiatives barely noticeable to the majority.

Despite everything, it is precisely these local engineering solutions that offer a chance that the future of plastic recycling will look like a network of compact, flexible platforms. And here, Liverpool is an excellent testing ground. If it works here – it can work anywhere.