Mineral extraction in Merseyside is an important topic with strong links to the environment. Our region was once home to coal mines where many people lost their health and their lives. Coal mining was a vital element of the economy in Liverpool and its surrounding areas, but it eventually exhausted itself. We invite you to explore the history of Merseyside’s coal mines at liverpoolname.com.

Early History

Coal mining in Lancashire, which formerly included Liverpool and many neighbouring settlements, has been carried on for many centuries, albeit on a limited scale. It is known that the Romans engaged in coal mining in Wigan. Furthermore, records from the 1300s concerning a ferry crossing on the River Mersey at Warrington mention coal from local mines. However, it is unknown whether this coal came from Wigan or St Helens. In the early periods, coal mining in St Helens was minimal; moreover, the mineral was of low quality and was mainly used for lime burning and by blacksmiths.

The first records of mining activity in Sutton Heath date back to 1540, when the Eltonhead family accidentally discovered a coal seam while digging a clay pit. As the family were tenants of the manor under Richard Bold, this led to a lengthy legal dispute. Eventually, the Eltonheads agreed to pay the landowner a commission for the commercial use of his territory. When the Bolds themselves began to actively engage in mining, it caused discontent among the residents of Sutton.

In documents dating from around the end of the 16th century, local residents sharply criticised Richard Bold’s mines. They complained that the mining had made getting around Sutton dangerous. One witness noted:

“Upon the said wastes, ways, lanes, and passages the ground is sunken… into deep pits whereby many of His Majesty’s subjects have been slain, drowned, or maimed.”

These records appeared almost 200 years before the advent of steam engines, which allowed for the development of deeper and safer mines. They tell us something about coal mining in Sutton. The geology of the land was always a critical factor for the success of any mining venture. Most coal seams in the Lancashire Coalfield presented significant difficulties for miners due to constant faulting and shifting of the rock.

Miners in Lancashire faced problems created by faults in the seams, which caused constant subsidence of the mine roofs and the ground above. For example, in the areas of Sutton Heath and Prescot Road, the rock was uplifted over millions of years, creating a geological fault line that runs through Croppers Hill and defines the northern boundary of the old Sutton township. These faults created serious obstacles for coal extraction, requiring miners and engineers to develop technologies to overcome these problems.

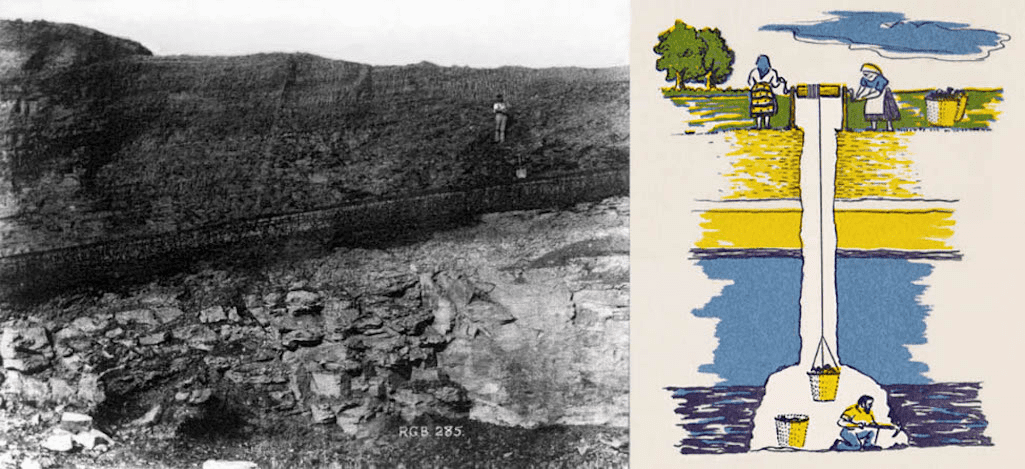

In the 1500s, coal was taken from where the seams outcropped at the surface and were easily accessible for open-cast mining with handheld tools. However, when miners saw that the coal went deeper into the ground at an angle, they began to dig vertical shafts (not to be confused with vertical farming). This was the first attempt at underground mining, known as ‘bell pit’ mining.

The gradual development of trade, the construction of canals and railways, and the Industrial Revolution made it possible to significantly expand coal mining capabilities. With the invention of the steam engine and the use of steel cables, it became possible to extract coal from deeper seams, which increased the efficiency of the mines and allowed for a better quality of coal.

Mines in More Recent Times: A Dangerous Job

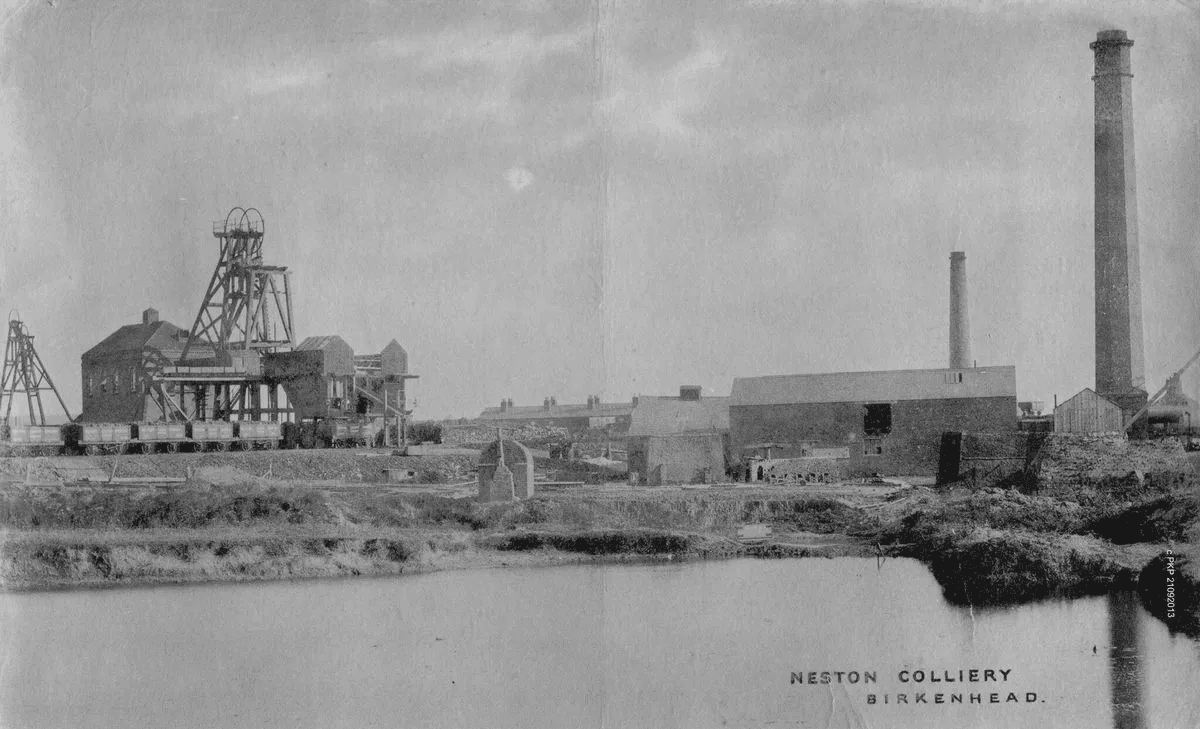

However, coal mines did not immediately become safe. Statistics show that at least 42 people, including children, died at the Neston collieries alone, which operated for over 160 years. Incidentally, this longevity is unique for the coal mines in our region; although there were many, others did not last as long.

Two Lives

The Neston collieries in Wirral are mainly remembered by those whose relatives worked there. The Neston Collieries had two lives. The first began in 1759 when the mine opened, just as the Industrial Revolution was getting underway in the country. The colliery operated until 1855 and made its mark on history by becoming the first major industrial site in West Cheshire and having the first steam engine in the region.

For a time, the Neston coal mines stood idle. They were revived 20 years later, in 1875, after which mining continued until 1927. The mine was a large and important local employer—at its peak in the 1920s, it employed over 300 people.

Unfortunately, like at many coal mines, people died at Neston Collieries. Statistics kept from 1759 to 1927 record the deaths of dozens of people, with the youngest victim of this ‘coal monster’ being a 9-year-old boy. In addition, hundreds of non-fatal accidents that resulted in injuries occurred during the mine’s existence.

From the History of Neston Collieries

The coal mine that opened in 1759 was known as Ness Colliery, and underground canals were used to transport coal to the Dee Estuary. A second mine, called Little Neston Colliery, operated a few metres away from Ness Colliery for about 30 years, creating unwelcome competition.

In that period, safety in the mines left much to be desired. People died for various reasons: a basket rope snapping during descent, a rockfall, or from explosions of firedamp (methane gas) or suffocation. There was a clear need to develop safety procedures and proper equipment.

The mining operation that began in 1875 was initially owned by the Neston Colliery Company but later changed hands to the Wirral Colliery Company. The mine was located at the bottom of what is now Marshlands Road in Little Neston.

A dedicated railway branch line was even built between the Neston mine and Parkgate, allowing coal to be transported to other railway lines. This ensured the delivery of coal from the Neston mine to homes, industrial enterprises, and ports in other parts of the Wirral and across the Mersey. It is believed that in the 1890s, the mine’s annual output was around 100,000 tonnes, but by 1923, it had dropped to 60,000 tonnes per year. On 12 March 1927, the last shift worked at the mine, after which about 180 people lost their jobs.

Revival of Industry at the Parkside Colliery Site

In 2023, news emerged that an industrial revival was taking place on the site of the former Parkside Colliery, which operated from 1957 to 1993. This was the last deep coal mine in Lancashire, and its closure symbolised the end of the region’s 700-year industrial history. During its operation, the mine employed up to 1,600 people, but it then lay dormant for 30 years. There were plans to transform the site into a strategic rail freight hub, but they failed to materialise.

In the 2020s, permission was granted for the first phase of the site’s redevelopment, including the construction of 93,000 sq. m. of new industrial and logistics space. The hope was to attract companies involved in advanced manufacturing and logistics to the site.

The Parkside project is part of the new Liverpool City Region Freeport, which has special provisions that grant a specific tax and customs status to businesses within its territory. These advantages include tax reductions, simplified planning procedures, and other business incentives.

Beyond the economic benefits, the environmental issue is crucial. There are concerns about a potential lowering of environmental and social standards in freeports. The current implementation of the Liverpool Freeport does not suggest this, but it is important to remain vigilant to ensure that the region’s industrial heritage, while boosting its economy, does not disrupt the ecological balance.